Dear Poets,

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?

This is the question that Mary Oliver asks at the end of ‘The Summer Day’. We discussed this poem and others this week in an online poetry session and then we wrote in response to the poem.

I wanted to share a few thoughts with you about this poem and others that we discussed.

Mary Oliver’s ‘The Summer Day’ and William Blake’s ‘The Tyger’ are both poems of wonder and questions.

The Oliver poem celebrates, with trembling awe, the complicated beauty of the world and wonders about the origins of things:

The Summer Day

Who made the world?

Who made the swan, and the black bear?

Who made the grasshopper?

This grasshopper, I mean-

the one who has flung herself out of the grass,

the one who is eating sugar out of my hand,

who is moving her jaws back and forth instead of up and down-

who is gazing around with her enormous and complicated eyes.

Now she lifts her pale forearms and thoroughly washes her face.

Now she snaps her wings open, and floats away.

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention, how to fall down

into the grass, how to kneel in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what else should I have done?

Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?

Beginning the poem with questions (such as ‘Who made the world?’) highlights the narrator’s almost childlike standpoint which leads to a wisdom framed with more questions at the end of the poem.

The whole poem exudes a sense of amazement, and at the center of the poem’s bewildered gratitude is the statement: ‘I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.’

There is something endearing and engaging about a narrator who admits to not knowing. This line is the gate which opens to the rest of the poem. A sense of being ‘blessed’ follows; although the narrator ‘does not know exactly what prayer is’ she is comfortable using the language of the sacred only after admitting that she doesn’t know how to pray. Somehow conceding that she does not ‘know’ leads to accessing a connection to the divine.

The holiness radiating out of this moment generates questions about transience and spawns that seemingly simple but deeply rich last question, ‘what is it you plan to do / With your one wild and precious life?’ This question echoes the last line of James Wright’s poem and also Rilke’s last line in ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’—each of these three last lines express the almost the same idea in different forms. (Contrasting the poems by Wright, Rilke and Oliver led me to wonder about other poems which end with the word ‘life’ and I could only think of one other – ‘Words’ by Sylvia Plath. It’s difficult to pull off the word ‘life’ in a poem but the words resonates deeply in Western culture. I think of the words in Deutoeronmy (Chapter 30, verse 19): Choose life.( וּבָֽחַרְתָּ֙ בַּֽחַיִּ֔ים). If ‘life’ can be placed in a poem in a way where it surprises then it’s worth trying. (See if you can use the word in a poem – preface it with other words that will make its appearance startle the reader).

The richness of Oliver’s question, in part, comes from the word ‘you’ (the first and only time this word is used in the poem) — the reader is challenged, startled into attention, when addressed with ‘you’ and is asked to look at themself. (Consider writing a poem where the word you appears in one of the last lines for the first and only time).

The other word which jumps out of this question is ‘wild’, a surprising and vital choice of language, disquieting, almost frightening. We are told that our lives are ‘wild’ – perhaps the word suggests that our lives, fragile and finite, can be cut off at any moment, like the grasshopper’s. The word also implies that we are not fully in control of what happens to us and to what happens around us. Life is fierce, rough, and phenomenally beautiful and exquisite. And wild – anything can happen at any moment: ineffably joyful moments or devastating and everything in between.

It’s hard to face it, life is brutal: we lose people we love. And we can’t deny the unspeakable injustices and viciousness taking place in the world. And we also can’t deny the utter radiance of the world. The narrator’s admission of not knowing followed by feeling blessed led to this final question: what choices will you attempt to make in your unpredictable, brutal, ecstatic, and finite life? (Try including the word ‘wild’ in a surprising place in one of your own poems!)

There are two other places I can think of (off the top of my head) where the word ‘wild’ appears in American poetry, and I can’t help but mention them here:

In Emily Dickinson’s ‘Wild Nights’, wildness is celebrated – it is awesome and luxurious, connecting and a bit terrifying, intimate and unfamiliar. And in the ending of Gerald Stern’s ‘The Dancing’, it’s a word of awe and horror.

Prompt:

After looking at the Oliver poem and the Blake poem (below) we wrote poems that began with questions and ended with questions and included a line in the center that began ‘I don’t know’.

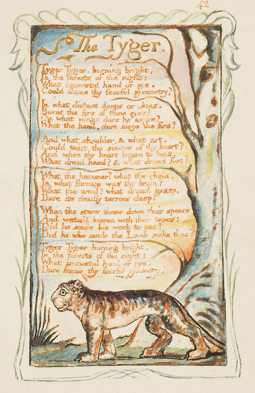

The Blake poem also asks childlike questions and focuses even more on wildness than the Oliver poem. It is much darker than ‘The Summer Day’ and in many ways more intense: Blake also wonders and asks questions about this world but it seems to me that the speaker is not just feeling awe and wonder but shock. It’s almost as if he can’t believe what he is asking. This shock is expressed in seemingly very simple questions, which I will paraphrase here:

1. How is it possible that a creature as beautiful and ferocious as a tiger exists?

2. Whoever would have created such an animal and how and why?

3. How is it possible that the lamb could have come from the same source as the tiger?

Here is Blak’es ‘The Tyger’ (his choice of spelling):

The Tyger

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat.

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp.

Dare its deadly terrors clasp?

When the stars threw down their spears

And water’d heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

‘The Tyger’ was the first proper poem I ever read. I was probably between eight and ten years old. I loved the image of the brightly coloured animal in the night forests. I didn’t understand much more than that although I probably intuitively absorbed some of its meanings.

Now, when looking at the poem, I am aware of the concentrated passion of Blake’s questions. This is the language of awesome intensity; the poem bristles with language like ‘burning’, ‘fearful’, ‘Seize the fire’, ‘twist the sinews’, ‘dread hand’ and ‘deadly terrors’. The narrator is expressing his absolute astonishment that the ‘immortal hand’ could create a creature of such ferociousness – his questions suggest that the creator might have these same qualities as well, which is terrifying.

He comes to the realization that the lamb, a very different kind of animal, also exists in the same world as the tiger. The origins of these creatures then is both gentle and fierce. How can such a contradiction be? Blake does not pretend to answer his questions. The whole poemis a series of questions that, like the Oliver poem, encourages the reader to step back and look at themselves, at their own animal qualities, at their own ferocity and softness, at their own questions about the sacred and this paradoxical world.

After our discussion about and writings from these poems we looked at the Sharon Olds poem below. It’s a poem that inspires us to look at ourselves, our animal selves, our denials, our loyalties, our attachments, our wild and precious lives and the choices we make (Olds uses the word ‘life’ three times in the poem’s two final lines).

I Could Not Tell

I could not tell I had jumped off that bus,

that bus in motion, with my child in my arms,

because I did not know it. I believed my own story:

I had fallen, or the bus had started up

when I had one foot in the air.

I would not remember the tightening of my jaw,

the irk that I’d missed my stop, the step out

into the air, the clear child

gazing about her in the air as I plunged

to one knee on the street, scraped it, twisted it,

the bus skidding to a stop, the driver

jumping out, my daughter laughing

Do it again.

I have never done it

again. I have been very careful.

I have kept an eye on that nice young mother

who suddenly threw herself

off the moving vehicle

onto the stopped street, her life

in her hands, her life’s life in her hands.

Prompt:

We wrote poems with the repeating lines ‘I could not tell’ or ‘I would not tell’ or ‘I will not tell’ or ‘I don’t want to tell’.

Finally, we ended the session by looking at a poem of profound gratitude and comfort. I often like to end the class with a poem of solace. It is possible to write such poems! ‘Small Kindnesses’ is below. It is written by Danusha Laméris. And here is a link to Helena Bonham Carter reading the poem.

Small Kindnesses

I’ve been thinking about the way, when you walk

down a crowded aisle, people pull in their legs

to let you by. Or how strangers still say “bless you”

when someone sneezes, a leftover

from the Bubonic plague. “Don’t die,” we are saying.

And sometimes, when you spill lemons

from your grocery bag, someone else will help you

pick them up. Mostly, we don’t want to harm each other.

We want to be handed our cup of coffee hot,

and to say thank you to the person handing it. To smile

at them and for them to smile back. For the waitress

to call us honey when she sets down the bowl of clam chowder,

and for the driver in the red pick-up truck to let us pass.

We have so little of each other, now. So far

from tribe and fire. Only these brief moments of exchange.

What if they are the true dwelling of the holy, these

fleeting temples we make together when we say, “Here,

have my seat,” “Go ahead—you first,” “I like your hat.”